Connecting objectives to requirements without losing the plot

In today’s fast-paced development landscape, aligning project teams with overarching business objectives is not just beneficial, it’s essential. These objectives exist independently of the tools, systems, or methodologies used to achieve them. Yet, in my two decades of experience, I’ve observed a recurring challenge: project teams often drift away from the strategic goals and become increasingly product-centric in their decision-making.

This misalignment can lead to friction, especially when the final product fails to meet the intended business outcomes. The disconnect between what is built and what the business actually needs becomes a source of conflict and inefficiency.

For this reason, a project manager has a key role in establishing a shared understanding of core terminology. By fostering this alignment early and reinforcing it throughout the project life cycle, teams can stay focused on delivering value — not just features. With that foundation, this article aims to explore a critical set of terms that supports this alignment.

Business objectives

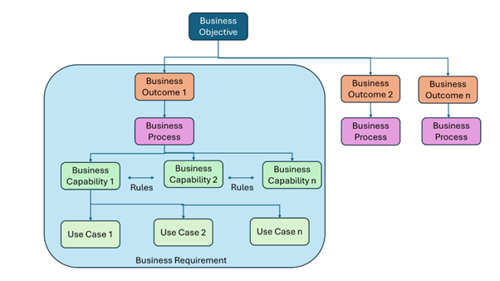

Business objectives represent the high-level, strategic goals set by the executive team to drive measurable impact on the company’s bottom line — whether through revenue growth, unit expansion, or margin improvement. These objectives articulate what the organisation aims to achieve, without prescribing how to achieve it. They serve as the guiding compass for all initiatives, ensuring that efforts remain aligned with the broader vision.

Examples of business objectives include:

- Reduce product return rates to below 1% in our consumer business model.

- Introduce a new subscription model leveraging our existing product portfolio.

Business outcomes

Business outcomes represent tangible, measurable milestones that mark progress toward achieving a broader business objective. Each outcome should be specific, quantifiable and independent — clearly defined in scope and not reliant on the definition of other outcomes to be meaningful.

A common pitfall is attempting to define an entire objective as a single outcome. Instead, it’s best practice to break down large objectives into a hierarchy of outcomes, each contributing to the overall goal in a structured and trackable way.

Example objective:

Launch a new subscription model using our existing product line.

Supporting business outcomes:

- Launch new subscription product lines for our hardware offerings.

- Subscription products should be available for both online purchase by customers as well as rep driven offline purchases.

- Launch new subscription product lines for our services.

By structuring outcomes this way, teams can focus on delivering incremental value while maintaining alignment with the overarching business objective.

Business process

A business process is a high-level visual map of interconnected activities that collectively drive a specific business outcome. It illustrates the flow of work, highlighting both manual and automated tasks to provide clarity on how operations are executed. The goal is to show how key elements like quotes or orders flow across functions like sales, processing and manufacturing — not to detail individual capabilities

In many projects, it's crucial to develop an "as-is" business process to capture the current state and then compare it with a "to-be" process that reflects proposed improvements or changes.

Capabilities

As we drill deeper into the structure of strategic alignment, capabilities emerge as the foundational building blocks that enable business teams to achieve defined outcomes. A capability represents a specific action or function that a team must perform — distinct from the tools or features used to execute it. A thoroughly documented business process naturally reveals a comprehensive set of capabilities required to support it.

One common misstep occurs when business capabilities are mistakenly framed as product features. This often happens within operations teams who have grown accustomed to a particular set of tools and begin to conflate what they need to do with how they’ve always done it. This confusion can create friction between business and product development teams, leading to misaligned expectations and delivery gaps.

Example outcome:

New subscription products should appear in sales catalogues for special pricing.

Supporting capabilities:

- Sales teams should be able to browse products by navigating a product tree.

- Sales teams should be able to search for products directly using Universal Product Codes (UPC).

By clearly defining capabilities, organisations can ensure that product development is guided by business needs — not constrained by legacy toolsets or assumptions. This clarity fosters better collaboration and reduces the risk of miscommunication across teams.

Business rules

Business rules define the conditions under which specific capabilities are applied or restricted. A critical aspect of any business rule is its scope — such as whether it applies to consumer customers, commercial clients, or another segment entirely.

One common challenge is the tendency to conflate business rules with capability definitions. This confusion can obscure the distinction between what a system is capable of and the rules that govern its behavior.

Example business rule:

Prevent the customer from accessing the payment screen (a capability) if the product quantity on the configuration screen (another capability) exceeds 50 — applicable specifically to consumer customers.

Business use cases

A use case serves as a practical lens through which business capabilities and their governing rules are interpreted across key business dimensions — such as customer segments (e.g., Medium Business vs. Large Corporations), customer types (e.g., End Customers vs. Channel Partners) and sales motions (e.g., Online vs. Offline purchases). It provides a structured opportunity for business teams to explore how capabilities and rules behave under various permutations of these dimensions. Documenting use cases in industry-standard formats like Gherkin helps ensure clarity, consistency and traceability.

Importantly, teams should embrace the creation of a comprehensive set of use cases — even if it results in some redundancy or overlap. This thoroughness helps uncover edge cases and validate assumptions.

Business requirements

Business requirements represent a comprehensive package of elements — including capabilities, business rules, process flows and use cases — that collectively define what is needed to achieve a specific business outcome. This integrated set of artifacts serves as the foundation for solution development, guiding the IT organisation in designing and delivering systems that align with strategic objectives.

Conclusion

Regardless of the chosen project methodology — be it waterfall, agile, or any hybrid approach — systematic documentation that connects business objectives to use cases is not just valuable, it’s indispensable. Project managers play a critical role in ensuring their teams understand and apply this terminology effectively across all deliverable artifacts. When this foundation is solid, the benefits are clear: fewer change requests, reduced defects and smoother project execution that stays aligned with business goals.

*written in collaboration with AI

0 comments

Log in to post a comment, or create an account if you don't have one already.