Defence project newbies: Is your project actually a programme?

Recently, I was tasked with establishing a brand-new aviation equipment department within a fast-paced engineering environment of a newly established organisation. I was given this responsibility without a formal theoretical framework or project methodology to guide me, without an official project manager title, nor an accredited project sponsor. Many will recognise this situation as akin to that of the accidental (or unofficial) project manager. I suspect many of my counterparts in the defence sector will recognise this 'no framework, just deliver' mentality all too well. We were just a growing team of professionals delivering engineering support to military helicopters, getting stuff done with limited resources in a fast-moving workplace context.

Initially, I approached the work as a project: defining outputs, creating a plan and driving tasks towards completion. It was only later while studying the APM Project Fundamentals Qualification (APM PFQ), which I had specifically sought out to gain this missing structure, that an epiphany struck: I realised I had not been leading a project at all. I had been managing a programme. Studying APM resources and learning materials really brought this home for me. And, importantly, that realisation was significant because it changed how I understood both the work and my role within it.

It is worthwhile looking at APM definitions and a useful model:

Project:. A unique, transient endeavour undertaken to bring about change and to achieve planned objectives.

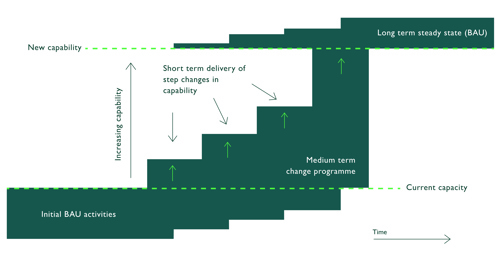

Programme:. A unique, transient strategic endeavour undertaken to achieve beneficial change and incorporating a group of related projects and business-as-usual (steady-state) activities.

My ‘project’ succinctly fit the definition, and this model, of a programme in its entirety. Once I recognised the key difference between a project and a programme, comparing theory with my reality, the work I was undertaking took on a different shape. Building this department from the ground up involved more than creating processes, practices, systems and checklists. The department delivery was, after all, enhancing the organisation’s effectiveness and facilitating incremental increases in capability. This meant focusing on outcomes rather than outputs and coordinating multiple interdependent streams of work, some of which were sequential and others in parallel, and teams of people.

The realisation and subsequent change in perspective consequently altered the way I engaged with stakeholders because it was no longer enough to report on task progress. What mattered was demonstrating how the initiative supported the strategy, identifying risks that needed attention and outlining how long-term benefits would be embedded. And conversations shifted from status updates to driving discussions about efficacy, alignment and outcomes.

It also reshaped how I saw my own responsibilities. As project leader I had thought of myself as someone who oversaw delivery. Through the lens of a programme manager, I had to find ways to navigate complexity, manage interdependencies, and guide people through friction, uncertainty, challenges, and change. I also had to support others, mentoring and developing people from different departments so that individual efforts contributed to the overall strategic goal.

Looking back, the switch from project thinking to programme thinking was, crucially, about adopting a different lens. Projects end when their outputs are delivered. Programmes endure through the benefits they leave behind. Recognising that difference made it possible for me to engage with governance and structure planning around outcomes instead of activities, and to engage stakeholders in terms of value rather than progress.

A key lesson I learned, and the one I hope is worth sharing, is that if an initiative feels larger than a project, it probably is. If its purpose is strategic, if it involves complex change, and if it requires the coordination of multiple related efforts, then treating it as a programme is likely a better approach. You’ll be less concerned with smaller details, more concerned with managing teams of people, and far more involved with interdepartmental business operations. This will bring clarity to how success is measured, strengthen stakeholder engagement and ensure that efforts deliver lasting value over succinct outputs. Projects produce results. Programmes build capability. The distinction lies in whether you’re managing activity or increasing organisational capability.

You may also be interested in:

- What is programme management?

- Explore our courses on programme management through the PAM Learning platform.

- Join the APM Defence Interest Network today

0 comments

Log in to post a comment, or create an account if you don't have one already.