Utilising rolling wave planning to meet funding challenges

The reality of critical national infrastructure programmes is that they are years long covering lifecycles of 10 to 20 years and there is a continuous conflict between the funding cycle and the planning process. While funding is necessary to progress, it is sometimes out of sync with the planning requirements of the overall programme.

As project, portfolio and programme management professionals, we know that we should only try to plan in detail what we can reasonably predict. Anything beyond this should remain in higher level planning packages, supporting the programme strategy and high-level objectives. As time progresses, we have a better understanding of how the work will be undertaken and can therefore plan in better detail, and with greater precision. This concept of near term detail planning and longer-term predictive planning will help keep project reporting and programme plans as realistic and accurate as possible.

The progressive elaboration of the detail plan is commonly known as ‘rolling wave planning’ and I’d suggest is the most effective way to approach the planning challenge of long complex programmes.

The Association for Project Management’s Planning, Scheduling, Monitoring and Control Guide states that rolling wave planning “describes the schedule density that is achieved at different moments in time”.

Leadership behaviours

Although we know the outcomes we desire, enterprise culture and leadership behaviours in projects frequently cause us to make decisions that solve a near term problem whilst generating a bigger one in the future.

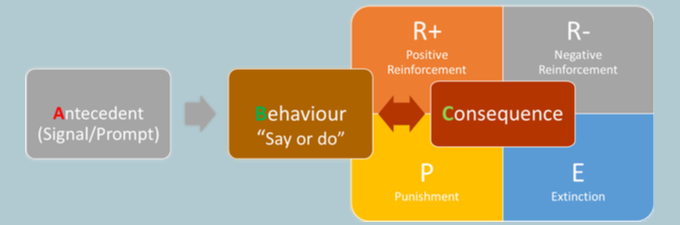

All behaviours are defined by a combination of inputs (antecedents) and anticipated consequences. As the figure below shows, the antecedent or prompt, influences the behaviour to an extent. However behavioural science has shown that it is the consequence, whether anticipated or actual, that has the greatest influence on behaviour. The nature of the consequence will impact the outcome and vary in effectiveness. The skill is knowing how and when to shape the consequence in order to achieve the desired behaviour.

Consequences with immediacy and certainty can consume attention, so although people try to deliver on target and message, the demands of today’s problem can draw focus from long-term thinking and problems are stored for later. Establishing a robust plan for a long, high-value programme is intuitively and logically attractive, however trying to plan in detail too far ahead could lead to the wrong decisions now.

Riding the rolling waves

Rolling wave planning is often operated as a continuous process and can result in continuous low-level planning, with packages being progressively ‘detail planned’ as they come over the horizon. However, this can mean a volume of changes being processed every month as more details are shared or finalised which can create a continuous administrative burden on the project team in terms of planning, review, and authorisation.

More mature applications of rolling wave planning will plan the waves in accordance with programme lifecycle (e.g. concept, definition, development, handover and closure - as defined in the APM Body of Knowledge) and associated major milestones. With this approach, every part of the programme is planned in detail (work packages and their activities) up to the next major milestone (e.g. preliminary design review (PDR)), against an agreed set of planning principles and programme assumptions. The remainder of the programme beyond PDR is outlined in higher level planning packages and milestones.

Once the programme has achieved the maturity required to clear the PDR, it would enter another wave of the planning process; the next phase between PDR and concept design review (CDR). This would be enabled by the project team stepping forward together using a common set of planning assumptions and behaviours.

In my opinion, the benefits of this approach are:

- Planning is undertaken in discrete chunks, aligned with the known scope (usually on contract) of the imminent phase of the programme. This reduces the level of up-front planning effort required.

- The detailed plan for the phase can be independently reviewed before execution of that phase commences. This delivers a higher confidence baseline against which progress can be assessed, and change can be accurately measured and controlled.

- Planning by phase is more likely to be based on better assumptions, estimates and understanding of programme maturity. Any experience from previous phases can be learnt and built into the next phase of the plan.

- Assessment and assurance activities examine the maturity, integrity, and completeness of the detailed baseline plan for the phase, using documented planning assumptions as a foundation. In this way, rolling wave planning can be supported by rolling wave assurance.

How funding can impact the programme

Programme planning is often aligned to programme funding cycles, and hence approval gates and phase contracts. Whilst this is intuitively a sensible approach, major difficulties can arise in practice. Customers require value for money and fiscal control; suppliers need long term visibility and certainty of business to satisfy shareholders and ensure continued delivery capability.

However, what unifies both customer and supplier is the need to apply rigorous programme management to deliver programmes on time and on budget – and ensure that what is delivered remains fit for purpose throughout the intended lifetime.

Few programme sponsors are willing or able to fully commit funding to the full duration of a long programme. In practice, this means that programme funding profiles are often misaligned with the ‘natural’ planning (including budgeting and contract/commercial) lifecycle.

Whilst there is an imperative to plan the full programme, in terms of work and resource (budget), taking account of rolling wave principles, there is a disconnect with the allocated funds. Whilst funds are categorically not the same as budget, funding does impact the actions a programme may take.

Back to basics

So – what’s the solution? Ideally, to separate the funding from planning as far as possible. In the extreme, planning can be done without considering the available funds. Clearly, the robustness of that plan will be questionable, but in principle, the plan can still be created.

The key is to remember the definitions and purpose:

- Budget cannot be spent – it is just a target.

- Funds represent money available for expenditure in the accomplishment of the effort. Funds are spent. Without funds, the programme cannot continue.

Not the same thing. So why treat them as if they are? In my experience, this important distinction is often overlooked or misunderstood.

The key is to ensure that the programme’s termination liability (essentially spend plus commitment) never breaches the limit of funding. Other than that, the plan is just an aspiration, a representation of the intended work and consumption of resources. Crucially – if the plan must change as a result of subsequent funding changes, it can.

- Discover more insight and guidance on how to apply rolling wave planning and assurance in our Right Result Playbook

- Find out how to be a great project leader with Claire Fryer, Gordon MacKay and Mike Bourne in the latest APM Podcast

Image: Costain

0 comments

Log in to post a comment, or create an account if you don't have one already.